By Alanna Smolarz

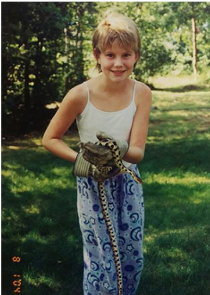

I have been spending summers at my cottage on Georgian Bay for as long as I can remember. There is no doubt in my mind that these experiences played a role in my career choice as a biologist. I still love catching turtles and snakes, but now it’s my full-time job! After completing my Master of Science at McMaster University in 2017 and working in my field for a year, I was lucky enough to land a job with the Lands and Resources Department at Magnetawan First Nation near Britt.

I have been spending summers at my cottage on Georgian Bay for as long as I can remember. There is no doubt in my mind that these experiences played a role in my career choice as a biologist. I still love catching turtles and snakes, but now it’s my full-time job! After completing my Master of Science at McMaster University in 2017 and working in my field for a year, I was lucky enough to land a job with the Lands and Resources Department at Magnetawan First Nation near Britt.

My commute to work from my cottage where I was staying at the time often meant I was driving the roads when turtle sightings are most common (in the morning and evening). In previous years, I had noticed countless nests along certain parts of Dillon Road that had been dug up and the eggs eaten by predators. In general, populations of turtles can withstand some level of nest depredation seeing as it is a part of the natural food web and provides a food source for predators like foxes and racoons. However, roadsides substantially increase predation rates. Road shoulders are a common nesting area because of the loose substrate (i.e. soil) and heat absorbed by the road pavement which provide ideal incubation conditions for the eggs. In locations where these ideal conditions are located along wetlands, or in the case of Dillon Road, cross large wetlands and bodies of moving water like the Shebeshekong River (with a single-lane bridge, no less), hatchlings are already at a much higher risk of being hit by cars when they emerge. Road shoulders are also more accessible to predators, and therefore tend to become a buffet-style resource for predators who quickly realize these areas are hotspots for nests. In these areas where predation rates may be unsustainably high, nest protection or other recovery strategies may be warranted (Ontario Nature).

With this in mind, I decided to take on a little project of my own last year to cage turtle nests along Dillon and Sand Bay Roads because I would be driving this route every day on my way to and from work. The cages I made are constructed of wood and chicken wire with a little exit for the hatchlings; I weigh them down with rocks to deter predators and put flags, reflective tape, and a little sign on each of them. While I worked along the road (with a safety vest on at all times of course!), people often stopped to say hello and ask questions. It was a good feeling to see the public getting interested! I had no idea, that I would stumble upon so many nests (25 to be exact), but the turtles just kept coming! There were nests of Snapping Turtles, Northern Map Turtles, Blanding’s Turtles, and Painted Turtles. One nest was unfortunately dug up by a predator, and one never hatched which could be the result of many factors: if the eggs were not fertilized, they will never develop; the nest location may have been too dry, wet, hot, or cold to allow proper egg development; if it was a Northern Map or Painted Turtle Nest, there is also a chance that those hatchlings will emerge this spring as these two species are sometimes known to exhibit this behaviour in northern populations. But in total, 23 clutches that I covered hatched successfully!

I was even more motivated to try and help because all of Ontario’s eight turtle species are listed as Species-at-Risk, both provincially and federally. This is a result of many factors including nest predation as well as habitat destruction, discriminate killing, and road mortality. These threats are magnified by the fact that turtles are extremely long-lived species which means that it takes a long time for them to reach an age when they can mate. The chances of making it to that age and surviving adulthood is extremely low, even in a balanced ecosystem without the threatening factors I’ve listed. Therefore, things like road mortality and predation substantially reduce their chances of survival to an upsetting low.

To put it into numbers, if the nest is not depredated and the eggs develop properly, given appropriate temperature and moisture conditions are maintained in the nest cavity, there is an approximately 6% chance of a single hatchling from that clutch surviving its first year of life. If it survives the first year, there is a less than 1% chance that it will reach an age where it can reproduce (roughly 20 years old). So, the chances that a single turtle egg will reach adulthood is much MUCH MUCH less than 1%. Based on research from the Algonquin Provincial Park on Snapping Turtles, it can take up to 1400 eggs for the chance that one of them will reach maturity and thus replace their mother in the population. However, even if this one egg survives to adulthood, it will only stabilize the local turtle population. In order for these populations to recover and grow, this number needs to double! It is also why it is so incredibly important to keep adult turtles alive because their existence is practically a wildlife miracle! Roadsides are especially dangerous to turtles as you can imagine. Adult turtles themselves are surprisingly terrestrial; females and males will sometimes make long overland trips to their preferred nesting areas and overwintering wetlands. This means that they often need to traverse roads and highways to get to these areas, thus putting them at risk of being hit by a car. The Ontario Turtle Trauma Center is a turtle specific animal hospital which will take injured turtles (such as ones hit on roads) and do their best to repair, rehabilitate, and return these turtles to the wild so that they can continue contributing to their population growth. For those asking why we’d want more turtles around, especially Snapping Turtles, did you know they are the janitors of waterways? Like most other turtle species, they eat dead animals and fish. They are quite docile if you don’t bother them and are often caught up in their own business of just surviving day to day. You also have to keep in mind that they were here LONG before us, so we need to learn to share our space with them!

As a biologist, I am sometimes overwhelmed with the environmental issues happening around the world today. Part of my job is to understand the impacts humans, development, and climate change are having on populations of reptiles and I can tell you it is quite concerning. When I am faced with these struggles, I remind myself that “every little bit counts” and even though I may not be making a huge dent in helping preserve turtle populations in Carling, I can at least say that I tried. If there was the slightest chance that you could make a difference, however small, wouldn’t you try? “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.” (Dr. Seuss)

I have partnered with the Biosphere Reserve to make and sell turtle nest cages that are available for purchase at their office at 11 James Street, Parry Sound, for a minimum donation of $15. All proceeds will go towards covering the costs of the nest cage materials and funding future turtle conservation work in the Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve. There are several citizen-science programs available where you can help researchers learn more about turtles in our area. These volunteer opportunities are done with as much or as little time you have available. Visit gbbr.ca/citizen-science to learn more or contact Tianna at the Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve: biologist@gbbr.ca. If you have any other questions, please refer to the online resources listed below or contact me at alannasmolarz@hotmail.com.

Resources

To read more and to download a PDF, please visit the WCA Spring Newsletter April 2020