By Skip Allen

It was a gorgeous Sunday in August 2012, when three unfamiliar boats pulled up to our big red boathouse on Bateau Island. The visitors introduced themselves as David Stewart, Donna McNeill and family and were just hoping they could see the cottage that used to be owned by their great-grandfather. My wife Lucy invited them up for refreshments, and after everyone was properly introduced (our cottage was full of family and guests that holiday week), we sat down to get a history lesson.

To our astonishment, they explained that their great-grandfather was the original owner of our cottage! Henry William Radcliffe Tisdall, owner of Tisdall Jewelers in Toronto, had purchased Parcel P&Q of Bateau Island in 1911. (We knew the Canadian Government had originally surveyed Bateau for 24 parcels in 1910, and that ONLY parcel P & Q were purchased before the Crown changed its mind and decided Bateau should stay a pristine wilderness because of its wetlands. But we never knew who the original owner was). Henry Tisdall was born May 27, 1864, died May 27th, 1926, and was married to Marie Alice Fiske. One of their daughters (Dora Dieudonnee) was the grandmother of our unexpected visitors. Henry’s brother was Dr. Frederick Tisdall, a famous Toronto Pediatrician, who invented Pablum.

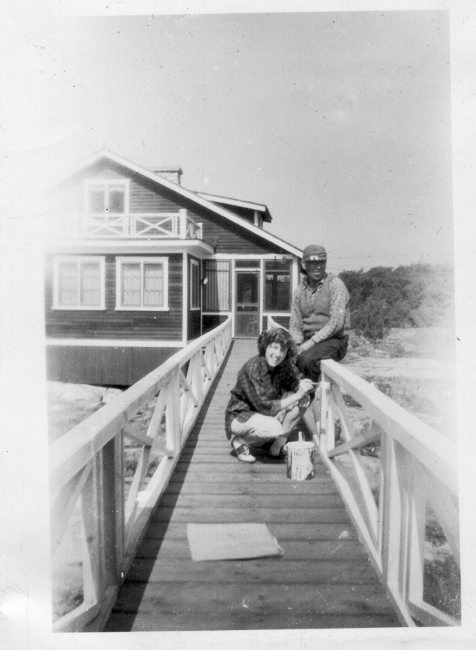

The visitors also recounted some unusual bits of family lore. In 1920 a pregnant young woman was walking from the cottage out to the ‘Teahouse’ and was bitten by a rattlesnake – she eventually lost her baby. This led to the construction of the original boardwalk (see picture) so as to avoid any such repeat of the snakebite.

Lucy gladly escorted our visitors around our 100-year old cottage, and then after exchanging addresses, we bid goodbye to our intriguing guests. Could it really be true that we share such a connection to our beloved cottage with strangers we had no idea even existed? Within a few weeks we exchanged additional emails with David & Donna, and to our amazement they eventually sent us pictures that made the Tisdalls strangers to us no more.

As thanks, we sent back to our visitors the following history of what had happened to their old family cottage after their great grandfather Henry Tisdall passed away.

The Ohmer Years (1926 to 1941):

Mr. W.I. Ohmer, like many wealthy Americans, vacationed in the Parry Sound area in the early 1900s. It was relatively easy to reach via cruise ships or passenger trains. Also the summers were cool, a major attraction for someone living in the hot, humid Ohio Valley. By the 1920s Parry Sound had several excellent hotels, including the Belvidere where Mr. Ohmer was a frequent guest of the proprietor, Mr. A. G. Peebles. In 1926 Ohmer’s love of the area soon led him to purchase his own cottage on Bateau Island (which we now know was from the Tisdall estate).

Wilfred Ignatius “Will” Ohmer, was born 26 April 1860 in Dayton Ohio. He initially entered his father’s furniture business, Michael Ohmer & Sons, and eventually became CEO. He invented the streetcar fare register, perfected in 1893, which was the forerunner of the taxicab fare register. In 1896 he was managing director of the Register Recording Company, London, England. At one time, he was also the owner of the Dayton Journal newspaper. His Gracemont Estate was in the ritzy Oakwood section of Dayton. He and his wife Grace Dana Snyder of New York City had one daughter, Grace.

Will Ohmer was good friends with the most famous inventors from Dayton, Wilbur and Orville Wright. When the Wright Brothers needed help patenting their new ‘flying machine’, they turned to their friend Will Ohmer. He took them to his lawyer outside of Dayton and in so doing started them on their journey to one of the most famous patents in all history. Orville Wright was also connected to Georgian Bay. He had purchased a cottage on Lambert Island in 1917 and legend has it he and Thomas Edison may have visited their friend Ohmer on Bateau.

By the late ‘30s Mr. Ohmer was nearing 80 years old and his health was deteriorating. In Aug 1941 he wrote a letter to his friend Mr. Peebles, who had helped Ohmer purchase the property in 1926, asking Mr. Peebles to help him now sell the cottage. (Our family still has a copy of this original handwritten letter – it shows the deep feelings that Ohmer had for Bateau, and the importance he placed on the simple pleasures it gave him.)

The Douglass Family Years: 1941 to Today

Our family’s connection to Georgian Bay and Bateau Island began when Mr. Will Ohmer, somewhat frail in his 81st year of life, walked into the law office of the Honorable Mason Douglass in Dayton Ohio. Ohmer was sure if Judge Douglass saw the island he would fall in love with it just as Ohmer had many years before. It was August 1941 and America’s entry into WWII was only a few months away – but Mason was intrigued, so he called his wife Jessie and told her to pack and get their twin daughters (Martha and Mary age 19) ready for a trip to Parry Sound, Ontario.

Their destination was Bateau Island. It was a 600- mile trip from Dayton Ohio to Parry Sound Ontario, but that was the easy part. After arriving at the town dock, they still needed to board a Livery Boat and head 30 miles out into the 30,000 Islands of Georgian Bay. The scenery was like nothing they had ever seen — pure clear water, smooth pink granite islands, windswept pines and hardly a soul in sight. After spending just a few short days on Bateau, the Livery Boat came back and returned them to civilization. But Ohmer was right, and the island spell had been cast. Mason & Jessie returned to Dayton and made the purchase that would come to have a profound effect on their lives, and those of their grandchildren, great-grandchildren and even great-great-grandchildren.

For the twin girls (Martha and Mary, who were still in college) those first summers on Bateau were a welcome respite from the terrible events gripping the world. Most of the boys their age were off to war, and some would never return. Bateau Island did “pitch-in” for the war effort. A Pine blight had struck the northern shores of Georgian Bay in the early ‘40s and now most of the old pines on Bateau and surrounding islands were dead. Mason gave the Canadian Government permission to build a small cabin on his Parcel Q and use it to house the loggers who would harvest wood for the war effort.

For Jessie Douglass, just in her early 40’s, the first few years at their new cottage on Bateau meant no running water, no toilets, no electricity, no outboard motors, no phones, no refrigerator, no restaurants and only a few nearby neighbours. Clothes were cleaned with a hand wringer and washboard. Meals were cooked on a wood stove. Food was kept in the Icebox using frozen blocks cutout from the lake and stored in the Icehouse. Jessie was strong and independent and would have made a great pioneer woman. She had no trouble embracing this somewhat rugged island life. In fact, she came to love it and would make this her ‘home away from home’ for the rest of the summers of her life.

When the war ended, gasoline rationing stopped and travel was easier. Jessie was now spending most of the summer at the cottage along with Mary & Martha, who had recently graduated from Ohio Wesleyan College. These two pretty, single young girls attracted their share of “visitors” — including a handsome young Ontario game warden who always seemed to need to check on the fishing near Bateau when the girls were around.

But the most important visitor came in summer 1948. Jessie loved company, and her friend Lucille Dietz from South Carolina visited with her that year. When it was time to go home, Lucille enlisted her husband Phil and her nephew Stone Bagby to come pick her up. Stone had been an Air Force Pilot flying ‘over the hump’ from India to China during WWII, so she figured he could navigate from South Carolina to Parry Sound.

We’ll never know whether it took Stone one minute or five days to fall in love with Martha L. Douglass during his stay on Bateau. But we do know when he returned home he told his mother he was “going to marry that girl”. On Apr 2, 1949, Stone Bagby and Martha Douglass took their wedding vows in Dayton, Ohio.

Jessie wanted to spend the whole summer at the cottage, but Mason was a practicing lawyer, so he could not be away from Dayton for such long periods. Mason knew no one should be staying in that ‘wilderness’ alone, so he hired Jim, a native Ojibway living on the Parry Island First Nation reserve, to keep the place open with Jessie from June thru Aug.

The small room at the back of our boathouse is still referred to as “Jim’s Room”, since that is where he lived during the summer months. There was plenty for Jim to do in those days. Wood for the stove, cold blocks from the icehouse, guiding fishing trips, maintaining all the wood boats, cleaning fish, and on and on. He was a very good carpenter as well. In 1947 Jim rebuilt the entire boardwalk using only a handsaw and hammer. The existing kitchen cabinets were also hand-built by Jim over 60 years ago.

Jessie may have been content with the simple cottage way, but Mason had some different ideas. In the 1950’s he began to add conveniences that many of the surrounding islanders thought were somewhat grand. Examples: Two Peterborough runabouts with 16hp motors, that some islanders predicted would pull the transom off the boat; a new Servel propane fridge to end the dependence on the icebox; a gas-powered pump, attic mounted water tank and a Septic bed that allowed for modern bathrooms to be installed. By the early ‘60s he had built a new Dining Room and added a large covered deck; extended the boathouse to 100ft to take care of the three new Thompson wood boats; added a massive front dock, and wired the cottage and boathouse for lights run by generator. They even added a Baby Grand Piano for the living room!

In those early days, all this earned the Douglass cottage on Bateau a bit of notoriety. Many of the other cottages still had outhouses, oil lamps, and just one small boat. In the early ‘50s, Mason purchased Barrett Island (“the little house”) from Charles & Lillian Noble to accommodate the many guests Jessie was inviting. Jessie often used it as her own retreat, and let her guests stay on Bateau. Mason renovated that cottage as well, and they owned it for 30 years.

Jessie passed away in 1972, and by 1980 Mason was in poor health. Like many family cottage histories, this meant a period of transition as the next generation learned how to maintain and share the cottage. Fortunately for our family, Martha Douglass’s bond to Bateau was very strong. She had met her husband Stone Bagby there in 1948, and she had continued to bring her children to the island every year. My wife Lucy, Martha’s oldest child, has essentially spent a portion of every summer of her life at the cottage. We now have four children (plus their four spouses) and three grandchildren coming to the cottage every year. Lucy knows that in a few years another generational transition is inevitable, so she makes sure to gather her grandchildren around the fire each July and tell them the stories first hand of how their great-great-grandparents Mason & Jessie Douglass and all their descendants came to love Bateau.

Footnote: Bateau and Dayton.

Many of the early nearby islanders (we now count ~ 15 cottages as neighbours) were also from Dayton — and were associated in some way with the Dayton Gyro Club. The Crouch’s and Millers had owned Killarney from 1926. The Grandins (Paradise) and Newells (Nutz Knob) came in the late 1930s. Byron Spoon (Spoonland) and Harry Brown (Evelyn Island) purchased their cottages just before Mason in 1941. The Robinsons, Gerard’s, Lohrs, Bates & Shorts followed in the late ‘40s, and then Watsons (Beacon Island) in late ‘50s. The Millers (leaving Killarney to the Crouch’s) set up the only other cottage on Bateau in 1960. Every one of these families was from Dayton.

Only six of those original families still own cottages around Bateau — Douglass, Newells, Spoons, Watsons, Millers, & Gerards. Each one of those families has a rich history of their own to tell.

Dayton Daily News Society Page announces Will and Grace Ohmer heading to summer cottage on Bateau Island (July 1928)

Jim’s rebuilt Boardwalk c.1950. Compare to Tisdall picture in 1920 — all the pines are gone due to the Pine Blight.